Perception, reality, and the fundamental scaling problem of teams and companies

Scaling an organization is hard. If you've done it, you know.

When you're small, the concerns are customers, product, strategy. When you're growing, those concerns remain, but a new class of problems emerges. Hiring is hard. Maintaining culture is hard. Creating an All Hands format that doesn't suck is hard.

It's hard because you're a different company. What was once a nimble raiding party has become a professional army. The latter can accomplish more, but only if its supply chains are in order. (It goes without saying that supply chains are hard.)

Given all this, it can be tough to step back and consider more philosophical problems: For example, what the heck is going on around here?

Working at a startup can be a magical experience.

There are several reasons for this, but a big one is the tightness of the "Decide-Do-Disseminate" Loop. That is, the moment you decide to do something, you can. Moreover, disseminating the impact of what you've done is painless. At a small enough company,1 everyone knows everything (or mostly everything). They even know the context — why something had to happen, the nuances and subtleties that made it difficult. Everyone decides, does, and disseminates together, and therein lies the magic. With minimal conscious effort, the company's perception of itself roughly corresponds with reality.

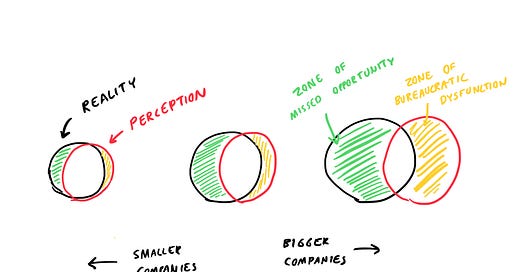

Or, to put it graphically:

In an environment like this, the pace of learning is extreme.

If you don't need to align on basic facts, assumptions, and jargon, you can ladder up to more complicated topics: "Was this initiative worthwhile? Is this customer worth catering to? Should we chuck our roadmap and pivot?"2

Then things happen.

A product takes off and you hire people to accelerate it; you raise money and bring on an expensive executive whose only real skill is building large organizations; employees see that executive and want their own opportunities to lead.

Overnight, you find that the beautiful, almost mysterious process of information dissemination breaks down. Even you, a company leader, don't always know what's happening.

In short, reality and perception begin to diverge:

As it does, discussions become more fraught. If you and your peers can’t agree on reality, then how can you decide that one project is more important than another? That one hire or partner is more important than another?

To “solve” this, companies begin investing in intentional communication processes, metrics, and OKRs.

The latter is often framed in terms of “sharpening our strategy!” or “empowering us!” or “our investors are making us!” But I wonder if bosses would succeed more if they said, “Look, we need to get a grip on what’s happening here.” (At least employees would feel justified in their confusion.)

Alas, were it only so simple. Although these actions help bind reality and perception more closely, they are themselves distorted by who gets to be in the Zoom room when decisions are made (to say nothing of the professional incentives of the people in that room).

There seems to be something fundamental about this problem. It's the corporate equivalent of gravity. The bigger you get, the more perception and reality diverge3:

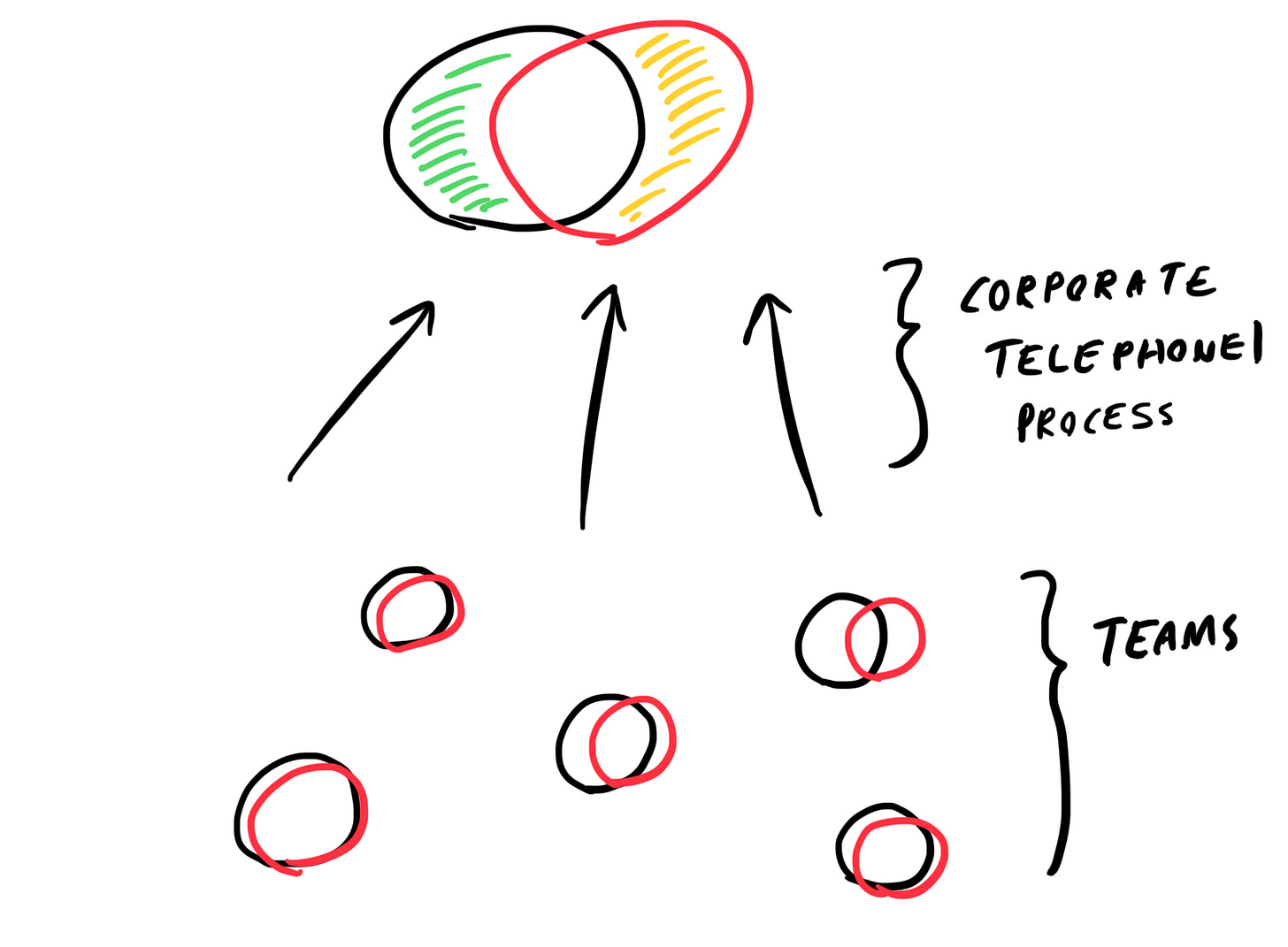

I will say something controversial and probably dumb: On its own, this might not be a huge deal? Even if the company can't see itself clearly at a high level, there remain teams within the company who know their individual slivers well:

So long as they're empowered to execute, they can continue to shape reality.

But, of course, small teams aren't always empowered. Things get dangerous — and indeed, company-killing — when employees and executives respond to this problem by worrying more about perception management than problem-solving.

It is here I must introduce one of my favorite concepts, Jerry Pournelle's Iron Law of Bureaucracy:

In any bureaucracy, the people devoted to the benefit of the bureaucracy itself always get in control and those dedicated to the goals that the bureaucracy is supposed to accomplish have less and less influence, and sometimes are eliminated entirely.

Pournelle makes it seem sinister, and sometimes it is, but I think the truth is duller: People want to have an impact. They want to be rewarded for that impact. They respond to the organizational incentives they face.

At a small company, where perception and reality are in sync, that means doing valuable stuff. At a medium-sized company, where perception and reality have begun to diverge but can be bound together with enough effort, that means doing valuable stuff and communicating its impact aggressively, annoyingly, and broadly. And at a big company, where leaders spend lots of time on process and things move slowly, that could mean — and often does mean — shaping perception itself.

If perception is up for grabs, it becomes rational for ambitious people (especially expensive executives) to use the bureaucracy's processes to their own ends.

What is to be done?

First, ask yourself: Do we need to grow?

I’m serious.

Everything is a trade-off. Leaders and managers often fantasize about what they can accomplish with more people but don't consider the downsides. Are you ready and willing to spend more time on your supply chains? If not, more people will slow you down, not accelerate you. Worse, you haven't been fair to your future employees.

Second, hold yourself and other leaders accountable. This might prove an unpopular take, but I think tackling this problem begins and ends with a company's leadership. Indeed, I’d go so far as to say that the mark of a good leader/manager is their ability to keep the “reality” and “perception” bubbles as close as possible for as long as possible. Whatever combination of culture, process, and organizational design makes that happen is ultimately on you.

It’s worth dwelling a moment on culture. If an employee can't count on leaders to seek out the truth and admit when they're wrong, perception management will rule the day. The times I've felt worst as a manager were when I cared about an initiative so much that I felt myself asking leading questions to see if there was a prism through which it could be considered "successful." But there is a difference between diagnosing why something failed and trying to spin failure, and it’s that difference — multiplied enough times and at enough levels — that prevents companies from seizing opportunities and avoiding dead ends.

Frankly, neither of these options is altogether satisfying. This is the fundamental unsolved problem of knowledge work. After all, if we're in the business of ideas, then building better mechanisms for determining the truth of those ideas is paramount. We should be experimenting aggressively.4

To that end, I’ll toss out some speculative solutions.

First, I've always been fascinated by the concept of internal prediction markets. Rather than rely on HiPPOs to make decisions, companies can pool the knowledge of their entire employee base to determine whether something will be a success. Is the CEO's pet project worthwhile, or did their executive team just nod politely when they pitched it? Moreover, as companies learn whose predictions are particularly valuable, they can weigh the votes of these superforecasters accordingly.

Second, I believe that data — both qualitative and quantitative — has an essential role to play. Even from an early stage, a company's organizational structure should communicate data's importance. It shouldn't be seen as "in service" of something else (i.e., sales or product) but valuable in its own right. The idea of a "Chief Insights Officer" is picking up steam, but maybe it should become as important a component of company-building as a Head of Engineering or Product.

These ideas are merely starting points. I don’t even know if they would work. (Anyone who’s been in a large organization knows that data can justify a lot of idiocy.) But we need to be ambitious. The modern technology company isn’t that old. Why accept it as fixed, especially as we move to remote and hybrid work?

It's a testament to human ingenuity that despite our countless cognitive biases, we've managed to scale teams, organizations, and societies as much as we have. I mean it: It's magical.

But if we want work to be a place that harnesses our capacity for creativity and problem-solving more productively, we can do better. The technology companies we're building today have a global impact. We owe it to the world to see that impact with clarity and seriousness.

Call this threshold Dunbar's number.

It also helps that there is endless opportunity. Since everyone can be doing so many valuable things, these discussions rarely become political. (If they do, run.)

I've often wondered if this helps explain why startups beat incumbents. People point to the power of focus and disruptive innovation, which are no doubt vital. Still, there is something about seeing the battlefield clearly that feels decisive.

I often ask myself why we don’t experiment. Certainly, one reason is that the people in charge of large organizations often get there because they’re really good at perception management. But an even bigger hurdle might be that human beings only care about truth insomuch as it has signaling value. Read The Elephant in the Brain for more on this phenomenon.