A/B testing can be a part of your product development process — but only a part

A/B testing is a remarkable tool. Assuming you have a well-formed hypothesis and take your Data Scientist’s annoying concerns about peeking, sample size, and novelty effects seriously, you gain knowledge that you can be relatively confident is true.

Since knowing what’s true is an essential part of making organizations successful, you can bet I’m a fan. (Also, I’m a Data Scientist, so I have a vested interest in A/B testing continuing to be a thing.)

The real returns to A/B testing accrue over time. As you and your organization make A/B testing a core part of your product development process, you develop a compendium of knowledge, the vast majority of which will also be true! Armed with a record of what’s worked and what hasn’t, you can more easily onboard new teammates and keep your roadmap free of frivolities.

The problem with A/B testing is that it is such a remarkable tool. Once your organization gets good at it, it becomes hard not to reorient your culture around the practice. When that happens — when A/B testing becomes an end to itself rather than a means to do better for your customers — your product development process is busted.

To make this concrete, let’s consider an example.

Meet Mr. Whiskers:

Mr. Whiskers runs saucy.io, a marketplace for cats to import fish from Japan. Business has been stable, but Mr. Whiskers wants to increase sales so he can impress the cats on MeowMix, the cat food brand/professional networking site for feline executives. He hires a growth team and tells them to get to work.

The team does an offsite and brings to Mr. Whiskers their first idea: a “freshness filter” that allows visitors to look only at fish caught in the past two days.

Mr. Whiskers is incensed! Fish is fish. Spoiled. Fresh. It’s all delicious. Why limit saucy.io’s inventory?

To convince him, the team gets permission to run an A/B test. The results are overwhelming. Sales rise 10% and repeat visitors skyrocket as customers return daily to see the latest catch.

Mr. Whiskers, now humbled, realizes that his intuition can be wrong. There might even be something profound about this “Scientific Method” that humanity goes on and on about.

He starts wearing a lab coat to work:

Mr. Whiskers uses the new revenue to hire more product teams. During orientation, he tells them that A/B testing is “How We Do Product” at Saucy. He even buys every new hire a lab coat to underscore the point, but his employees routinely “forget theirs at home” to avoid offending their boss.

But then something funny happens.

As the larger, more scientific saucy.io runs test after test, racking up “wins” that organizationally savvy PMs turn into promotions, the company begins to fall behind its rival, fishy.co.

Mr. Whiskers is shaken. “How could this be happening?” he asks. “It’s all anyone is talking about on MeowMix. I demand an answer as soon as I wake up from this nap!”

The Head of Growth rushes to put together a presentation. Multiple people use the phrase “all hands on deck” on Slack. There is much political gamesmanship as VPs try to defray blame from their organizations (or at least themselves).

Eventually, a narrative emerges: The A/B tested wins were “real,” thank goodness — there’s no statistical chicanery going on. But as saucy.io was busy optimizing its current product for its existing user base, fishy.co was expanding the market of online fish buyers with innovative products like “Find Your Fish,” a box that combines several different fish from a rotating cast of fish suppliers, replete with beautiful, artsy cards that describe different preparation methods and white wine pairings.

Customers who felt intimidated by the “hardcore” saucy.io flocked to fishy.co, which had rebranded itself as “The Friendly Fishmonger.”

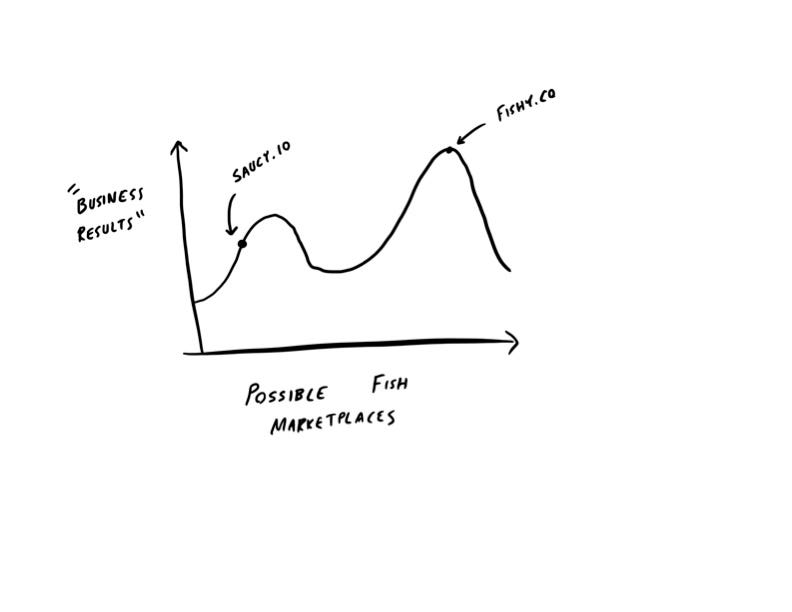

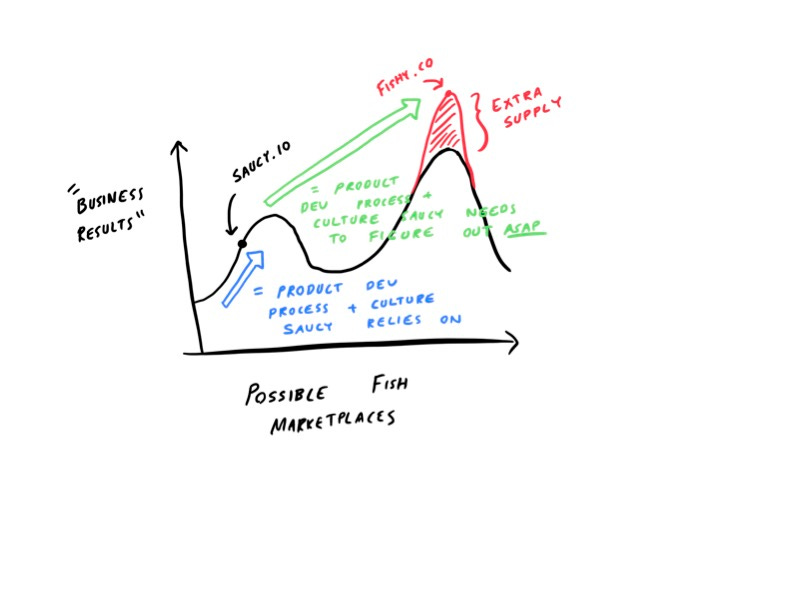

In other words, saucy.io had been so busy optimizing its narrow slice of the fish market that it missed the more significant opportunity at stake:

But it gets worse!

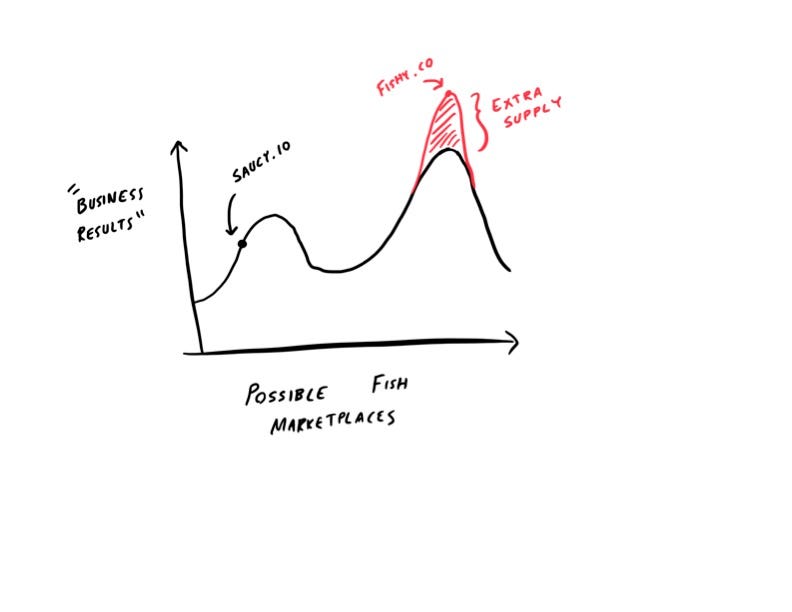

As fishy.co developed new ways of encouraging customers to try more fish, suppliers began begging to earn spots in upcoming boxes like “You’ll Snapper This Up,” “Tuna Value,” and “Holy Mackerel!”

Such a supply shock wouldn’t show up in the context of an A/B test, but it would show up in the strength of each company’s business:

Indeed, these supply dynamics will likely decide which company wins the market in the long run. After all, fish enthusiasts might prefer saucy.io and its extensive collection of filters, but if there’s a better selection at fishy.co, they’ll still need to switch.

Mr. Whiskers wakes up. He licks his paw while listening gravely to his team’s presentation. When it’s over, he darts underneath the nearest couch so he can think.

On the one hand, it’s obvious what saucy.io must do. It needs to be bold. It needs to fight for the suppliers it lost. But Mr. Whiskers is a keen student of organizational psychology. He knows that A/B testing has become core to the way his company functions:

How do we resolve disagreements? Run a test.

How do we decide on one course of action versus another? Run a test.

How do we determine who gets promoted? Well, who ran the most impactful tests?

Mr. Whiskers realizes that he was seduced by A/B testing not for its truth-telling power but for its ability to be an organizational salve. He deluded himself into believing that A/B testing would lead saucy.io to victory, but by nature, A/B testing doesn’t “lead” anywhere. It optimizes. It fleshes out. If done perfectly well (which is hard!), it helps your product become the best possible version of what it already is. If done poorly (which happens all the time!), it turns your product into what it already is, plus a bunch of annoying growth hacks and dark patterns.

A/B testing focuses your company on one question: “What will move the number in the short-run?” But that’s another way of asking: “How do we climb this hill?”

That constrains the options your company considers, which can be nice for strategic, organizational, and even personal reasons. A constrained search space is more straightforward to traverse and produces less controversy during the traversal. Moreover, it allows you to trick yourself into believing that you’re a detached observer, simply there to be a conduit for the most “data-driven” decisions. Numbers drive consensus, and consensus is pleasant. But being obsessed with consensus is like being a politician who decides what to believe based solely on polling results. You need to lead — your team, your product, and sometimes even your customer.

Sooner or later, your company will need to learn how to search beyond where it feels comfortable. That means having productive disagreements about nebulous strategic problems. It means knowing whether you’re catering more deeply to your current customer or appealing to a marginal one. It means operationalizing the ability to progress toward more speculative goals, including knowing when to abandon them and shift course.

At the risk of overloading the graph we’ve been discussing, it basically means this:

If your company doesn’t learn how to leap from one mountain to the next, it will never thrive, especially in a fast-moving market like fish delivery.

Mr. Whiskers rises; he stretches. He looks out the window of his office tower and takes in the view of the San Francisco Bay. The Golden Gate Bridge glitters in the distance.

“If a species as dumb as humanity can build something so beautiful,” he says to himself, “we can change the culture at saucy.io.”

Is this example too stylized?

I mean, yes, there’s a talking cat named Mr. Whiskers. But the themes are broadly applicable.

Consider everyone’s favorite corporate punching bag, Meta.

In the company’s Q3 2021 earnings call, Mark Zuckerberg mentioned that the company would be shifting its KPIs from “overall user growth” to “young adult user growth” (emphasis mine):

And during this period, competition has also gotten a lot more intense, especially with Apple’s iMessage growing in popularity, and more recently, the rise of TikTok, which is one of the most effective competitors that we have ever faced. Though we are retooling our teams to make serving young adults their North Star, rather than optimizing for the larger number of older people. Like everything, this will involve trade-offs in our products and it will likely mean that the rest of our community will grow more slowly than it otherwise would have. But it should also mean that our services become stronger for young adults, this shift will take years not months to fully execute, and I think it’s the right approach to building our community and company for the long term.

Funnily enough, after years of ruthlessly optimizing the Facebook platform, they had built the perfect product for the olds (myself included). That it alienated young users in the process isn’t a mistake — it’s a consequence of data-driven product development. Older adults are, on average, wealthier than younger adults, and, like Mark Zuckerberg said, more numerous. Thus, to the extent Meta optimized for revenue, they necessarily nudged the product toward the larger, richer group. Like saucy.io, Meta made choices that allowed their competitors to peel away underserved customers.

Of course, like Mr. Whiskers, Mark Zuckerberg might have avoided this fate by leveraging data more intelligently. They could have measured supplier bargaining power. They could have segmented their user base more thoughtfully. They could have forced teams to analyze every A/B test with an eye toward how it impacted new v. existing users, young v. old users, or high-value v. low-value users, and only shipped those that didn’t excessively privilege a particular group.

All of this would have been helpful, but here’s a surprise: I don’t blame either executive for failing in this regard. Have you worked in an organization of human beings (or cats)? Subtlety and nuance are really hard, and at the end of the day, you need to empower an organization to make decisions at scale. The alternatives — analysis paralysis or overly complex decision-making frameworks — are also bad. The problem isn’t giving individual teams operating clarity; it’s allowing that clarity to lead to a suboptimal product.

That’s the real lesson for Mr. Whiskers and Mark Zuckerberg.

For what it’s worth, I have my doubts about Meta’s ability to change course, even with new KPIs. So long as it’s the same culture driving the same product development process, they’ll be attempting to A/B test an old folks’ home into a place where teens want to hang out.1 I would place significantly more trust in a design-oriented company like Airbnb, which recently unveiled a remarkable transformation to focus on categories. That’s something that was likely data-informed but could never have been completely data-driven.

This real-world example might be more fraught than my stylized one.

It’s easy — distressingly easy — for A/B tests to be short-run positive but long-run neutral or negative. For example, an algorithmic change might cause a site to show more political content, causing people to flock to it so they can keep tabs on the incorrect opinions of their childhood friends. Over time, however, as people associate the experience of using a site with downer posts about politics, they might use it less, then less, then not at all.

But by then, the directors who presided over these pyrrhic victories have segued them into VP-ships, allowing them to repeat the cycle with even more influence.

Thus, it’s not just that A/B testing constrains your search space but that it does so in ways that might pit your employees’ interests with those of your company and customers.

That’s a thought that should cause every product leader who’s overly reliant on A/B testing to dart underneath a couch.

I feel the need to reaffirm something: I love A/B testing. Some of the coolest professional moments I’ve had are learning something I didn’t expect or analyzing a test in ways that informed future product iterations. I also think the failure modes of a data-driven company are better than the failure modes of an “intuition-driven” (i.e., the HiPPO decides) company. At least A/B testing provides a pseudo-objective framework by which to adjudicate decisions. (I poked fun at Meta above, but they built a world-straddling colossus, whereas I’m a humble Data Scientist writing a blog on the internet.)

A/B testing is a superpower.

But therein lies the danger: It’s so easy to lean on our superpowers.

It’s true that Facebook famously nailed the transition to mobile and undercut Snapchat by copying its core feature, so I’ll probably regret saying this. Still, the competition Meta is now facing seems like a new thing under the sun. Changing KPIs (how the company handled mobile) and copying (how it handled Snapchat) don’t seem sufficient to the scale of the problem.