A grand unified theory of why everything sucks now

Humanity faces a polycrisis: Environmental catastrophe, institutional dysfunction, economic stagnation, and the lingering physical and psychological health effects of a pandemic whose lessons we failed to learn are only some of our interrelated problems.

Sad as it is to live in a time of polycrisis, it’s sadder still to feel like we can’t attempt solutions. Gone is the society that passed Civil Rights legislation and removed Nixon from the White House, as evinced by the fact that no one — not even our politicians and business leaders — can imagine us achieving anything comparable today.

But why? What happened?

The reasons are varied, but a big one is that solving problems requires functioning consensus-building mechanisms. Only by seeing reality for what it is can we change it. But the tools we’ve long relied on for grasping the world’s complexity — media, democracy, talking to a neighbor — have been broken by for-profit, ad-driven social media platforms.

I’m not the first to blame social media, of course, but I don’t think social media is necessarily evil. I don’t even think algorithmic social media is necessarily evil. The problem lies specifically in ad-driven business models that segment and alienate their users to create economic value.

To state my contention directly: The economic logic of digital advertising treats human beings as raw material for a process of algorithmic manipulation. This process aims to convert that raw material — us — into maximally profitable advertising targets, which it accomplishes by personalizing our information environments.

If a happy and well-informed population were maximally profitable, that’d be great — we’d be manipulated accordingly. But alas, humanity seems neither happy nor well-informed. That’s because the qualities that make us good advertising targets — predictability, pliability, gullibility, and insatiability — are bad for human thriving and horrible for human agency.

Manufactured goods have no agency.

Before you dismiss me as a Luddite, allow me to explain.

Even in the old days (e.g., the 90s), companies advertised. They had products (e.g., beer) and found content whose viewing demographics aligned (e.g., NFL games).

The causal chain was relatively pure:

Content existed.

That content attracted an audience.

Advertisers wanted to say things to that audience (e.g., “Whassup?” ):

Crucially, the content and audience came first. Only then did advertisers follow.

Suppose you’re an advertiser who must take an audience as given. In that case, you have only two options to improve the return on your advertising expenditure: you can find content with a different audience or make better ads.

But what if you had a third option? What if an audience could be changed by the content they consume, becoming more appealing advertising targets in the process?

For example, a Budweiser executive could rely on a content creator to subtly alter its offering to reinforce aspects of a consumer’s identity that correlate with beer drinking. Maybe some consumers drink beer when they feel distressed, so for them, the cameraman lingers on injured players writhing on the ground. Other consumers might prefer to drink in fits of machismo, so they frequently see players celebrating after violent hits. And, of course, for many consumers, drinking pairs perfectly with envy, so the cameraman pans to a picture-perfect family taking their baby to her first football game. (Of course, the cameraman scanned the viewers’ Google search history and knows they’re struggling with infertility, which makes his camerawork particularly effective.)

You get the point I’m making by now, but think about what a profound development this is: We could nominally experience the same product but feel completely different emotions. I might be outraged by a dirty hit, you, anxious about an unfortunate injury.

Neither of us realizes that our emotional responses are downstream from a complex optimization function that takes into account our likelihood of buying beer, insurance, and movie tickets.

Algorithmic media is quite good at manipulating our emotions to make us better consumers. But its power doesn’t end there: It manipulates the events we see, full stop.

Returning to our personalized NFL game, the score might appear artificially close to keep viewers engaged and consuming more beer ads. In the extreme, maybe depressed beer drinkers see their teams lose while celebratory beer drinkers see their teams win.

But, surely, you say, that’s a bridge too far! There’s one score! People will always agree on such basic facts about the world.

When the truth is subordinated to profit, facts are merely one more vector algorithms have to maximize the likelihood of a click. Sometimes facts are helpful, and sometimes they’re not, but never are they core to an algorithm’s optimization function.

It’s obvious why manipulating someone’s emotions would be valuable for advertising. There’s a reason Facebook once bragged about its ability to make people sad.1 But why sever someone’s connection to reality?

Algorithms don’t do this intentionally, of course. They test inputs (i.e., content), observe outputs (i.e., dollars and engagement), and iterate. Thus, it could be as simple as lies being more engaging than truth for a subset of users.

That’s undoubtedly a factor. The more algorithms entice us to stay online, the more profitable we become.

Still, I wonder if there’s a more profound logic at work. When an algorithm divorces us from reality, it becomes the sole arbiter of our worlds. That increases its scope for manipulation, which is handy for maximizing revenue.

If I might invoke a silly parallel, it reminds me of the famously ridiculous Nigerian scammer emails: the ridiculousness is the point. Scammers know that if someone responds to something so obvious, they’re manipulable. Similarly, it’s useful for algorithms to know who their dupes are. Dupes are, by definition, pliant and predictable! If an algorithm can produce dupes at scale, all the better.

I should pause here to add some nuance to my story: Advertising has always influenced the content we consume. Soap operas got their name because CPG companies conspired with TV networks to produce never-ending series that would attract the homemakers who bought Proctor & Gamble products (including soap). Fox News daily reminds its audience that the world is ending, which is convenient given that its advertising partners sell gold, home security, and other products one needs at the End of Days. (Also, pillows for some reason.)

In other words, content is always made with specific commercial segments in mind. Once that segment has been captured, the same processes we’ve been detailing — emotional manipulation, spreading misinformation, etc. — may be employed to maximize its value to advertisers.

The difference now is three-fold: First, manipulation is mandatory. Soap operas hooked homemakers but didn’t manipulate homemaker identities to make them likelier to buy detergent. Second, the returns to manipulation are higher. Since online ad inventory is infinite, algorithms have an incentivize to keep us scrolling. Thus, they optimize for “time spent online” (i.e., addiction) rather than subtler but more meaningful forms of user value (e.g., am I happier, more connected, better informed, likelier to renew my subscription, etc.). Finally, manipulation is precise. For all its sophistication, Fox News must pick a single set of programming for one large audience. Whether someone is a bog standard Republican or a January 6 apologist, they see the same thing. If Fox News wants to add more content, it bears additional costs, limiting its programming possibilities.

None of these constraints apply online. Algorithms are free to identify the End of Days Threats from an endless supply of costless content that speak directly to someone’s most fine-grained demographic, psychographic, and behavioral characteristics. Worse, if someone is at all predisposed toward destructive but profit-maximizing views, algorithms will figure it out and manipulate them accordingly, one piece of content at a time.

To be clear, I don’t mean there’s some deterministic path to radicalization. Ultimately, algorithms don’t care if you become a Proud Boy or a Golden Retriever enthusiast. They simply want to sand down your edges until you’re a clean input into ad bidding markets. The argument here isn’t that algorithms necessarily drive us to ruin. It’s that they don’t care if they do.

Would changing the business models of our tech titans away from advertising solve these problems?

To be honest, I don’t know. But I suppose I’m convinced for a few reasons.

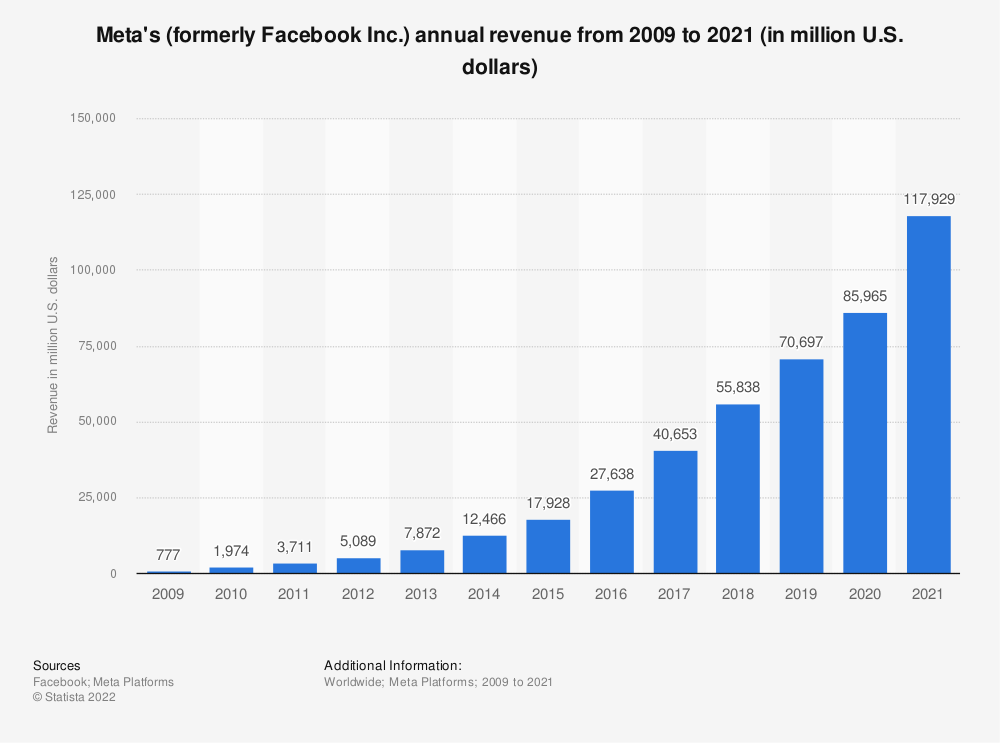

First, think back to Facebook’s evolution. The company introduced the algorithmic News Feed back in 2009, but, at least in my recollection, the service didn’t become socially corrosive immediately. Not until Facebook began ramping up revenue growth around its 2012 IPO did our politics deteriorate.

To say nothing about teen mental health2:

Second, advertising has always been about the creation and exploitation of customer segments. Digital tools simply supercharge the process. Targeted ads help determine our social labels, while personalized media that primes us to think about our social labels makes us susceptible to targeted ads. In other words, targeted ads and personalized media jointly create tribes they can mine for clicks and dollars. Humanity is already vulnerable to in-group/out-group thinking. It seems weird to inflame the impulse by making it the target of the most powerful artificial intelligence systems ever to exist.

Finally, think about the other algorithms in your life. (Sorry for writing the most dystopian sentence of all time.) Netflix, Spotify, Amazon, Stich Fix, and countless other companies personalize their offerings to make them more relevant to their customers. But we are their customers — not advertisers. The algorithms only work if they serve our interests. Granted, they may appeal to parts of ourselves that we’d prefer to keep in check (e.g., my Netflix feed includes a lot of terrible reality TV), but I can at least be confident that they’re trying to decide what I want, not what advertisers want me to become.

I would go one step further: I’m okay with targeted advertisements in specific settings. Concretely, I don’t care if Apple uses my previous app downloads to advertise new apps to me; however, I do care if Apple manipulates my Apple News feed to make me a better advertising target. Restating my contention with more precision: Ad-driven business models are destructive to the extent they corrupt our information environments. Information is too core to our evolution as individuals and societies.3 And while humanity couldn’t be driven to its present derangement if it weren’t by nature predisposed, there is something to be said for moderation. Not everything should be taken to its logical conclusion, but taking things to their logical conclusion is basically the job description of an algorithm (and capitalism, for that matter).

There is a fascinating literature in anthropology about the impact of wars, natural disasters, and other calamities on societies (e.g., here). At the risk of oversimplifying, they make tribes come together.

But we just lived through a pandemic, and I don’t know about you, but I feel no closer to the American tribe than I used to. If anything, it’s the opposite. Our divisions feel more glaring and incompatible than ever. The evolutionary response to trauma — what I remember feeling after pre-social media catastrophes like 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina — has been short-circuited. I wonder if young people even know what I’m talking about.

But then, isn’t that the Grand Age of Personalization at work?

I’m not part of the American tribe. I’m part of the YIMBY tribe, the Data Scientist tribe, and the new parent tribe. I’m part of the Blue tribe and the smart-people-who-got-vaccinated tribe. Why come together when our differential responses to the pandemic are such robust data by which to segment and optimize?

As I said, humanity is prone to every flaw that algorithmic media exacerbates. We are tribal, emotional, selfish, prone to mass delusions, and much else besides. I dramatically invoked the idea of polycrisis above, but our ecological and economic challenges have been a long time coming. It would be silly to blame technology companies for every bug in humanity’s operating system. But for all its flaws, the human OS has been good at patching itself when new information comes in — until now. The pandemic proves that new data cannot trigger updates like it used to. It will reach us if and only if it has a representation in algorithmic space that keeps us stagnant, divided, and engaged.

Coming together isn’t profitable, and because it’s not profitable, it’s not possible. Polycrisis is one thing, but polycrisis mediated through an algorithmic haze of strife and division is another.4

It might seem ironic to be writing this at a time of layoffs and declining advertising growth. Don’t these signal that the dam is breaking?

Maybe. Humanity is good at building social antibodies, and we’ve had more than a decade to learn how to cope with our new information environment. Maybe we’re waking up to its effect on our mental and social health and restructuring our digital worlds accordingly.

But I fear it’s the opposite. Big tech companies are pulling back because they’ve won and need to consolidate their gains. They’ve colonized our attentional landscape and must prepare for the long haul — a slow, relentless, and desperate grind for whatever growth can be squeezed from the stone of the attention economy.

That’s where I worry. Desperation won’t make big tech companies better social actors. Even more disconcertingly, they have powerful reinforcements coming. Generative AI will produce content that supercharges their ability to manipulate. Ad-supported metaverses will build us Personalized Mind Palaces that drag us deeper into digital derangement.

This is not the end of an era, it’s a beginning.

Still, we should take some time to mourn what we’ve lost — common ground, shared reality, all the banal terms for the hard-to-articulate idea that we need a foundation from which we can move civilization forward.

Or, if I could put it in a simpler and stupider way: We can no longer say “whassup” to our neighbor and be confident they’ll know what we mean.

That, more than anything, is why everything sucks now.

Thanks to Allie, Jerry, Melanie, Nikhil, and Thomas for the conversations and feedback that led to this post.

I’ve come to think that our worsening mental health and the explosion of mental health apps share a common cause. Digital media caused the former by facilitating the advertising model that allows the latter to find customers.

FWIW, TikTok, which today seems like a relatively joyous place, will undergo the same evolution when it begins to monetize in earnest. The only difference is that the algorithm will weigh the interests of the Chinese government against those of advertisers when making editorial decisions.

Indeed, quality information is essential not only for human beings but for the new class of AIs that are beginning to accomplish remarkable things.

In this interview, Stability AI CEO Emad Mostaque discusses the need for “clean data” when training sophisticated AI agents. Shouldn’t we treat the data affecting our brains with the same seriousness?

Sometimes, I comfort myself by thinking about the invention of the printing press, which made humanity go crazy there for a century or two (see: post-printing press Europe and its many witch hunts/religious wars).

Eventually, we developed social norms that could contend with a new information environment, which yielded tremendous benefits.

Check back in 2250!