On the origin of the self-hating Millennial technologist

Marc Andreessen and Andrew Chen, two venture capitalists (read: content creators) of the venture capital (read: content creation) firm a16z, recently sat down to discuss various tech topics primarily related to gaming. At some point in their conversation, they turned their attention toward the “self-hating Millennial technologist,” their term for Millennials who work in tech but feel conflicted about it, perhaps because they’ve internalized negative messages about the industry from a hostile media.

Andreessen’s theory for this phenomenon was more nuanced than I expected. He argues that Millennials are a “socially activated” generation. Since we lived through traumas like the Great Financial Crisis and the War in Iraq, we know how bad things can go, and — relative to Gen X-ers — are more likely to make a stink when they do. Andreessen generously goes on to say that Millennials include many intelligent and idealistic people who take their work seriously but that, in practice, this seriousness is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it makes for effective founders and employees. On the other hand, it leads Millennials to absorb too readily the anti-tech messages of the lame-stream media.

“Be proud!” Mr. Andreessen might admonish us. “You have nothing to apologize for! Ignore the lame-stream media and keep building!”

(To be clear, no one on the podcast used the term “lame-stream media”; it just seemed like maybe they would have liked to.)

I will not be totally snarky: There is wisdom in Andreessen and Chen’s perspective. The internet constantly transmits strange messages — about work, politics, parenting, sunscreen. Assuming you’re sufficiently neurotic/earnest, the algorithms will ensure you see the negative ones you’re most susceptible to. Some of these might worm themselves into your brain, making it hard for you to effectively lead your life/engage in proper skincare.

Still, I feel compelled to respond to this discussion because I’m arguably the subject in question.

To wit: I quit finance because I couldn’t stomach how parasitic the industry had become and how little value it provides its clients (let alone society). Since then, I’ve worked exclusively on utopian tech products. At best, I feel painfully ambivalent about the tech industry’s broader impact (and remember that ambivalent means “holding contradictory views,” not “indifferent,” which is the way it’s commonly used.)

It’s not that I don’t love technology — I have since I first played Donkey Kong on the SNES. I just notice that technologists working on ad tech too readily place themselves in a long line of innovators like Edison and Salk even as their inventions do nothing to boost American productivity.

All to say, I have some theories about why Millennial technologists might skew self-hating.

The primary explanation is simple: We grew up on the internet. We saw what it was before it was transformed by the most profitable corporate interests in human history. We witnessed — and later contributed to — its degeneration from a human-centered network into an algorithmic panopticon.

How could we not feel conflicted? We helped kill the thing that made many of our childhoods wondrous. Now we live with the consequences, caught between an older generation that came of age in a pre-internet world and so doesn’t take its devolution personally and a younger generation that seems vaguely dissatisfied with the status quo but doesn’t know that a better online world is possible. That we had it and lost it.

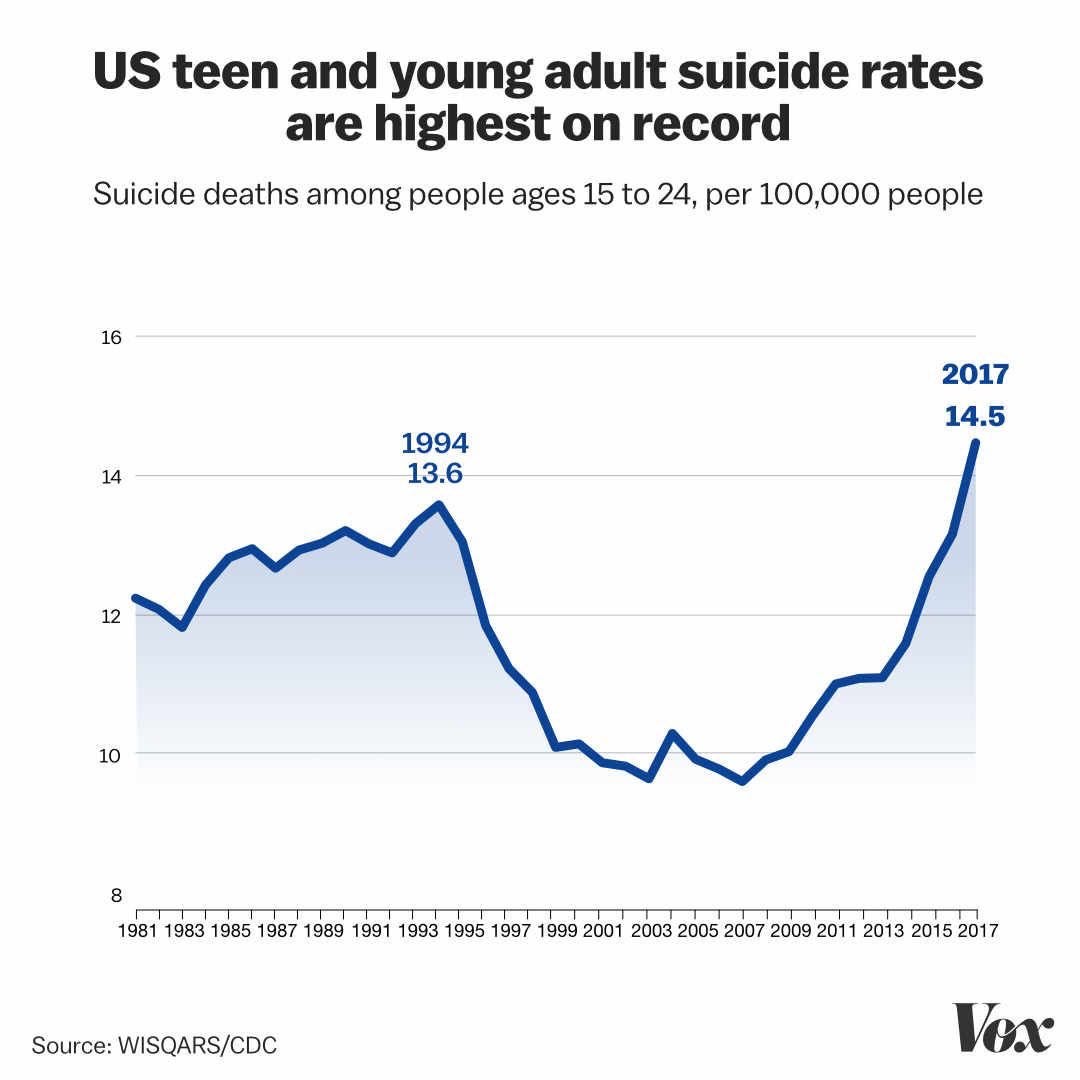

I’ve seen a graph floating around recently. It shows that Millennials grew up in a golden age of adolescent mental health, unique among the generations:

One could tell many “just-so” stories about this graph, and the real explanation is almost certainly too complicated to casually summarize in a few words. Cultural and economic factors, not to mention the interaction thereof, likely played the definitive role. Or maybe Jersey Shore did. I dunno. But I’d say that a small part of the explanation must be that we grew up during a unique moment in humankind’s technological evolution. When online connection complemented but didn’t substitute for real-world interaction, and indeed encouraged it. When the internet gave us freedom from prying adult eyes but hadn’t yet swapped their monitoring with a much more invasive kind. When we could use the internet to find ourselves rather than be defined by algorithmic manipulation.

Alas, I must admit that I’m emotional — even angry — about this graph, and emotion has always been gauche to discuss online:

Some might say my anger stems from being “socially activated.” And that’s probably true. But here is some additional context:

I am the child of Egyptian immigrants. While I now possess a firm grasp of American culture, for the longest time, I didn’t. Elementary school was isolating, and for several boring/banal reasons, I also felt alienated from my family’s primary social touchpoint, the Coptic Orthodox Church.

Again, nothing atypical. Standard “betwixt two worlds” immigrant kid stuff.

In an earlier era, this would have been my life until I went off to work or college and discovered something greater. But then the internet happened. My parents brought home a Gateway computer in the mid-90s, and my world changed overnight. Suddenly, I was plugged into a vast web of people — real people — governed by all the petty concerns that have long shaped human behavior but who hadn’t yet begun modifying their personas to please algorithmic interests.

From this network emerged something beautiful, almost pure: an ever-churning process of playing and writing and fighting that helped us — helped me — make sense of the world. Explanations for confusing American cultural quirks. Context about my own religious upbringing. The joys of computer programming. Good music. These were all gifted to me by an internet unashamed of its utopian dimensions.

And why would it be? The internet didn’t begin life as a commercial entity; it didn’t need to become one now.

Anyway, you know what happens next.

While I would never begrudge anyone making money on the strong foundations afforded by competent government research, I sometimes wonder what my process of self-discovery would look like today. Less pure, certainly, as the things I uncovered would be whatever algorithms sought fit to summon from the army of content creators fighting every day to game them. Opinions would be impossible to divorce from their popularity and status. The times in adolescence when one needs desperately to retreat from the world to find one’s place in it would have been disheartening. The defining characteristic of our era is that the hive mind’s judgment is inescapable. Even if one disconnects in theory, there is no disconnecting in practice: We all live with the mental model of a billion souls waiting to judge.

No teenager should live with that specter permanently haunting them.

I should be clear: Overall, a world with today’s version of the internet is still better than a world without it. It’s still the best tool we have for harnessing human potential.

Moreover, adolescent identity has long been shaped by commercial (and governmental… and religious…) interests. Any musical genre that teens like is proof of that (RIP nu-metal). But it seems inhumane to commercialize the process of identity formation so thoroughly.

The internet was built on that most essential human need: social connection. And connection has always been governed by a mix of transactional and non-transactional factors. The difference now is that the latter feels squeezed from online life. We are always and everywhere a number representing our profitability to platforms. Engaging in a process of self-discovery means fighting against the algorithms designed, above all, to maximize that number.

Am I overstating my case by looking back on the early internet with rose-tinted glasses? Doesn’t everyone think the world peaked when they were a teenager? Yes, and yes. (FWIW, I know people dunk on the nostalgic impulse, but my comically half-baked theory for why nostalgia is evolutionary adaptive is that people want and need a certain amount of constancy in their lives to feel comfortable having kids and prolonging the species, hence why countries that saw the most considerable amount of generational change due to economic development — Korea, Japan, China, etc. — saw the steepest declines in birth rates. But that’s a massive digression.)

But allow me to make two additional points that put my argument into still greater context:

First, consider this op-ed by Tali Sharot and Cass Sunstein, which argues that one of humanity’s defining qualities is our adaptiveness; we can habituate to circumstances far outside our current experience, so long as those circumstances come about gradually. At the risk of reducing the piece to parody, their point is that the Nazis don’t just show up one morning and start being evil. Rights are dismantled bit by bit; citizens acquiesce little by little. The water heats up, but at no point does the frog realize it’s boiling.

If you dropped a technologist from 1995 onto today’s internet, they would wonder why we’ve let ourselves boil. We’d have to explain that we don’t feel it: We adapted product launch by product launch, A/B test by A/B test, algorithmic tweak by dehumanizing algorithmic tweak.

Second, much has been made of the rise of the group chat, which has seemingly replaced the public internet as the dominant force shaping culture and opinion. In my own life, I’ve benefited from chats built around music, fatherhood, UCLA sports, fantasy football, and more.

The notable thing about this rise is that it just sort of… happened. Everyone seemed to grow sick of the internet simultaneously. People didn’t like the way it made them feel, and they wanted to stop wondering if their interlocutors were saying things they believed or things algorithms rewarded.

No one likes living in an algorithmic panopticon, so we hid.

The great group chat migration of the 2020s is probably healthy. But it’s still a bit sad. It means we couldn’t sustain the dream of the old internet. Commerce killed it, and now we’re mammals hiding out in caves as we wait for the asteroid’s after-effects to drive the dinosaurs to extinction.

One day, maybe a new corporate structure, regulatory regime, or product will revive the dream. It’s possible to imagine an OpenAI-style “profit cap” or a more robust antitrust framework restoring sanity to online life.

For now, my hope is that the child of Egyptian immigrants growing up today — probably in Houston because California is too expensive — finds the community he needs to make sense of his world. Hopefully, I’m worried for nothing.

Regardless, I promise I won’t try justifying Limp Bizkit next.