In a healthy company culture, status should accrue to problem-solvers

Status and Culture by W. David Marx is the book to read if you want to understand the status dynamics governing the evolution of art. But since you’re reading a loosely professional blog by a data scientist, I can’t be sure that’s what you want.

So allow me to make a rickety comparison that connects the thing I wish to talk about (artistic evolution) to the activity you’re statistically likely to be doing (white-collar work).

A central lesson of Marx’s book is that status accrual in the art world is highly contextual (or at least it was until the internet herded humanity onto three websites). Artists belonged to scenes, earning the respect of peers and critics by solving their scenes’ specific problems.

For example, punk rockers like The Sex Pistols earned status in 1970s London by making stripped-down DIY music that responded to what they perceived as the overly polished music then dominating the charts. Punk music — raw and direct — gave voice to a generation’s economic disillusionment in a way progressive rock never could.

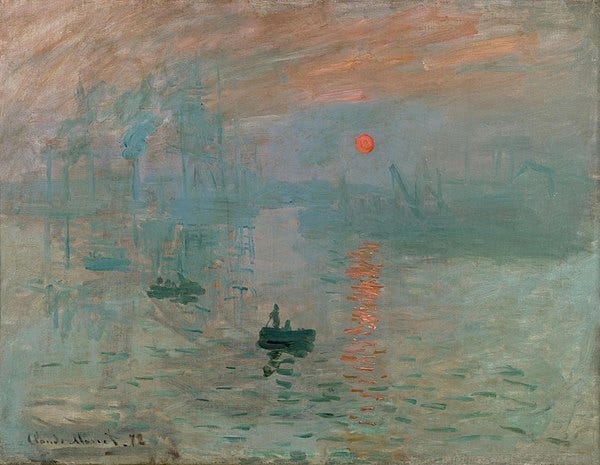

Similarly, Impressionist painters broke away from Parisian art school dictums to find new ways to depict daily life. By shunning realism, they conveyed aspects of reality that prior artists couldn’t.

The Sex Pistols don’t have much in common with Claude Monet, but they shared an ability to nudge their scenes forward in ways that spoke directly to the accomplishments of their predecessors and the challenges of their peers. Thus, we remember them today.

The context presents a problem; an artist dares to solve it; the scene moves forward.

Beautiful, right?

Is he ever going to connect this to my life, or…?

Yes.

I find Marx’s thesis compelling — so compelling, in fact, that it inspires me to propose a new way of evaluating company cultures: Namely, in a healthy organization, status should accrue to problem-solvers — to the people who are brave enough to point out where a company is going awry and creative and competent enough to fix it.

It seems obvious, even banal. Aren’t companies always supposed to reward their problem-solvers?

Maybe, but how many make it their explicit goal?

Like… really make it their explicit goal?

In too many companies, status accrues in sloppier and more unintentional ways — to the people who send the most Slack messages, for example, even if those Slack messages don’t represent a productive use of organizational time; to the people who make the best decks, regardless of whether the initiatives in those decks go anywhere. Status accrues not to the problem-solver but to the talker, the politician, the self-promoter, the gamer of corporate processes, the people who pretend that problems don’t exist and rah-rah their way into greater responsibility. Often, status accrues to the people who most remind the CEO of himself.

Of course, some of these qualities correlate with problem-solving to varying degrees, but such correlations inevitably break down as companies grow large.

Now, any executive coach worth their weight in LinkedIn followers would read the prior paragraphs and chuckle: “That’s life, kid. Adapt or die.”

You won’t hear any pushback from me (although I’d quibble with the dramatic, LinkedIn-friendly phrasing). Making one’s impact known is crucial. Occasionally, that means sending a few more Slack messages than seems strictly necessary.

Being gauche can advance your career.

But even if playing the corporate game makes sense at the individual level, it doesn’t address the context: the corporate organism as a whole.

Companies routinely miss out on harnessing their employees’ potential by failing to reward problem-solving in all its forms.

Of course, it’s all fine to say that “status should accrue to problem solvers.” The problem is operationalizing it.

Unlike artistic scenes, whose members share endless amounts of context (and possibly romantic partners), the modern corporation encompasses every conceivable function — from engineers to marketers to, uh, digital employees? Such disparate functions may not even agree about what a company’s problems are, let alone how to solve them. In such a multidisciplinary landscape, assigning reward is fraught.

So one option is to keep status accrual primarily functional. For example, some companies implement “promotion committees,” usually involving senior members of some function who opine on the worthiness of a promotion candidate’s work. In Marxian terms, they’re fellow artists assessing and appreciating (or not) their counterparts’ problem-solving abilities.

There is something to the idea (hence why many large organizations implement it). Only functional counterparts possess the artistic credibility and competence to assess the technical contributions of their team members. Moreover, most companies implicitly assume that via OKRs and other cross-functional processes, employees are necessarily working on the right problems. Thus, the magic really is in assessing how those problems have been solved. Promotion committees are eminently capable of such an assessment.

The downside is that they can tend toward myopia or even snobbishness. Maybe they reward “elegant” solutions and insular process improvements instead of ones that drive the business forward. Senior designers might look for junior designers with similar aesthetic judgment, failing to appreciate which part of that judgment is mission-critical versus personal.

In artistic terms, promotion committees risk becoming poetry, which many critics argue has become too abstract and detached from what ordinary people would recognize as art. In narrowly focusing on the problems of their field, poets now create work primarily for other poets.

The other extreme involves making promotion decisions cross-functionally, e.g., by leveraging a “calibration committee” involving senior managers across the company. As someone who’s sat in on some ludicrously painful versions thereof, I can tell you that these processes fail when leaders issue high-level assessments of people’s contributions with precisely zero of the expertise necessary to provide a substantive opinion. (You might assume that leaders should possess the self-awareness not to opine on things they know little about, but alas, over-confident opinion-sharing is what many companies select for when building management teams. Such organizations would be better off choosing managers by lottery!)

Calibration committees can be well-managed — I’ve seen versions of those, too. (They just require more prep-work than most organizations seem willing to do.) Still, at their best, they make it easier to reward actual business impact.

This push-and-pull between context-heavy functional evaluation and context-light cross-functional assessment reflects the uncomfortable fact that there’s no perfect way of apportioning status in a big group of human beings. (Hence why humanity created the idea of royal families — sure, it’s not fair to arbitrarily imbue certain genes with mythical status, but it’s a nifty way to avoid conflict and sell British tabloids.)

In the corporate context, a combination might be the best way we can do. For example, many well-functioning companies leverage functional processes for lower-level promotions and cross-functional processes for higher-level ones, the argument being that a promotion candidate should have a broader impact as they ascend within a company’s status hierarchy.

Of course, my analogy between corporate and artistic status accrual breaks down at a certain point. (Some would say immediately, but to them, as always, I plug my ears and go “la-la-la I can’t hear you.”)

First, in sketching my argument, I quietly swapped “status” with “promotion and calibration.” Promotions don’t have a true analog in the art world (maybe prizes?), so my focus is a matter of writerly convenience: It’s easier — and possibly higher-leverage — to consider corporate processes explicitly meant to render judgment. Still, the most vital forms of corporate status accrual works in more mysterious ways — just like in art. Everyone knows who “That Engineer” is, and even if they don’t, the hushed tones with which he or she is commonly referred to convey respect better than any title could.

If a company wants to produce more of That Engineer, it can’t rely on process alone. Managerial taste and cultural values are vital.

Second, and more substantively, artists often create work alone. When they make art together (e.g., in a band or rap duo), they are typically apprised together.

Sure, André 3000 might get more critical respect (and shoutouts from Eminem) than Big Boi, but reasonable commentators must acknowledge that there isn’t an Outkast if Big Boi isn’t writing the hooks. (André made a pan flute album, for Chrissakes.)

Contrast this with Corporate America, where we’re evaluated as soloists even though the whole point of business is making music together. Yes, there will sometimes be the perfunctory question on a 360 review template asking if somebody is a “Team Player,” but such questions seem small in the grand scheme of corporate work, where success fundamentally comes down to how individual players interact on the court.

Oh, God, oh, no, he’s building up to a sports analogy now, isn’t he?

Yes, sorry — might as well overload this post further.

In the vast majority of cases, we are basketball players, not tennis players. If I score 50 points in a losing effort, the effort doesn’t matter. No problems have been solved.

That’s not to say we should ignore individual excellence and initiative: Everyone on the Golden State Warriors knows that Steph Curry is their superstar. But we must be careful: As much as CEOs of a certain stripe like comparing their companies to basketball teams, they often ignore one ludicrously simple fact: Basketball is a game of clear and simple-to-measure outputs (e.g., points, rebounds, etc.), making it easy (although far from trivial) to determine who one’s superstars actually are. There is no simple statistic like “offensive rebounding rate” in the corporate context, and that changes everything.

Thus, I’ve always been intrigued by evaluation mechanisms that reward teams instead of individuals — that account for wins as well as points. Research/common sense indicates that these provide a more suitable framework for propagating high performance throughout an organization; however, like many seemingly obvious changes to corporate life, this one is too scary for (bold! ambitious! actually-profoundly-cowardly!) executives to try.

Such changes would also face sociological and psychological hurdles.

An underrated factor behind corporate stasis is that executives fear changing the system that birthed them. With every social or technological change, they implicitly ask themselves: Would I still be me? (Hence why the C-Suite embraces AI even as they rebel against remote work — the former supercharges our hero by giving him an army of error-prone drones to do his bidding, while the latter prevents him from dazzling his superiors with face time.)

Team-based performance management is especially threatening for our hypothetical executive because it undermines the Great Man Theory of Corporate America in which he alone makes things happen.

And although I’m picking on him (I love picking on him), it’s not totally his fault: American culture is individualistic, for good and ill. Our cultural operating system might not support a program of communitarian evaluation, even if it leads to a more direct and healthy alignment between individual activity and corporate success.

If you take anything away from this post, I hope it’s this: Life is context.

We identify and solve the specific problems posed to us at particular places and times. The only thing we can hope for us is that the right people notice and reward us accordingly.

May you one day find or create the environment that allows you to produce the white-collar corporate equivalent of Impressionism, Sunrise or The Sex Pistols’ “God Save the Queen,” both seminal works in their respective scenes.